SICOT e-Newsletter

Issue No. 46 - July 2012

Orthopaedics in Disaster AreasÂ

Within the scope of the collaboration between MSF and SICOT, we have published the reports of two SICOT members who participated in a natural disaster mission in Haiti two years ago. We have now received the report below detailing the experience of an orthopaedic surgeon in a war theater. Here all problems are multiplied by the high number of deep wounds caused by bullets and blasts in addition to the unsafe conditions.

Basic training of medical teams is required even more during times of war than it is after natural disasters. Dr David Nottâs description below is self-explanatory. Thanks to his experience he was able to improve basic health care in these very difficult circumstances.

During its annual meetings, SICOT will continue to deliver basic step-by-step training to enhance the preparation of civilian orthopaedic surgeons volunteering for these missions. The symposium presented in Prague on Amputation will soon be published in the International Orthopaedics journal. At the SICOT Orthopaedic World Conference in Dubai we will have a symposium on Triage and an instructional course on Natural Disasters.

Also on the SICOT website you will be able to apply to join the MSF/SICOT volunteer team on standby for future missions.

We would like to express our thanks to Dr David Nott for sharing his experience in this MSF humanitarian mission in Misrata, Libya.

Maurice Hinsenkamp

SICOT President

Trauma Skills Training at the Height of War

Trauma Skills Training at the Height of War

David Nott

Consultant General Surgeon, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital,

Consultant Vascular Surgeon, Royal Marsden Hospital & St Mary's, London

Senior Surgeon, Médicins Sans Frontières

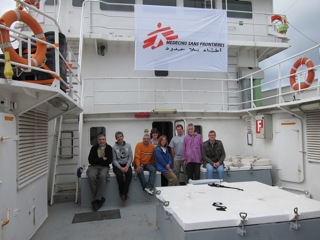

At the beginning of March of this year, I was asked to go to Misrata, Libya by Médicins Sans Frontières (MSF) but due to the uncertain security, the mission was postponed until the end of March. A team was put together consisting of two surgeons, two anaesthetists, an emergency department doctor, a scrub nurse, two general nurses and a logistician. The team left Malta in a fishing vessel and arrived at the port of Misrata some 17 hours later. The port entrance was heavily guarded by rebel forces and we very slowly entered the deserted harbour, the damaged buildings bore witness to the heavy bombardment over the previous few weeks. Significant logistical support provided by the headquarters in Paris ensured that all the warring factions knew that MSF was coming to provide humanitarian aid to the civilian people. Our mission was to provide surgical relief to the medical staff at the two trauma units created in the centre of the city in what were originally Al Hickma and Al Abbad private clinics taken over by clinical staff after the main hospital had been destroyed. There had been intense fighting around Tripoli Street and many people had been killed and wounded in the previous few days including the renowned British war correspondent Tim Fetherington. There was continual bombardment of the city by forces loyal to the government and tank shells, rocket propelled grenades and grad missiles constantly rained on the city. The front lines were around 12 km from the main hospitals at this time.

Triage was performed mainly by medical students at both hospitals and each hospital had around 100 beds. Al Hickma Hospital had four operating theatres and Al Abbad Hospital three operating theatres. There were no paramedical or nursing staff, as these expatriates had left at the start of the conflict. All nursing roles on the wards and all sterilisation duties for the operating theatres were performed by medical students in their third, fourth and fifth years. Misrata at that time was a city of 600,000 people and it was estimated that more than 1,000 people had been killed and over 3,000 wounded. Because all communications had been cut by government forces and neither cellphones nor the Internet were operational, the only way that casualties could be brought to the hospital was through word-of-mouth by ambulances driven by personnel with no medical training, only knowledge of the location of the fighting. Fragmentation wounds from rocket propelled grenades, mortars, grad missiles and also from direct tank fire using 50 caliber weapons produced horrific wounds. Many people bled to death at the scene, because of delays in transporting the patients to the hospital and also due to a lack of knowledge of the basics of airway, breathing and circulation. Others died en route to the hospital because of catastrophic bleeding from compressible sources in the limbs.

Â Â

One can imagine the situation whereby surgeons trained in routine elective work and occasional blunt injury trauma management found themselves in the middle of a war, which many had never experienced before. Not only that, surgeons who had come to help from other countries could operate but had never been in an area of intense conflict, where anxiety from hearing shells landing all around sharply focuses the mind on one's own vulnerability.

Triage was not understood, nor how to categorise patients into T1, T2, T3 and T4, particularly to differentiate between the T3 walking wounded and T4 frankly dying and then sorting the T1âs from the T2âs was a priority for teaching. In the operating theatre, chests were being opened when a chest drain would have sufficed. Internal cardiac massage was performed from the right chest without opening the pericardium. Abdomens were opened but the knowledge of how to stem the haemorrhage was lacking. Arterial bypasses were performed without fasciotomies. Fracture management was performed using nails and plates. War wounds were insufficiently debrided and the cardinal sin of closure of the wound was performed too frequently. There was no prior knowledge of damage control or damage control surgery. Patients were being discharged home without proper wound care and no possibility of further management of their massive wounds, which lacked skin cover.

Â Â

Having recently been in Geneva with the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) on a war surgery course, I had with me a USB stick containing the course and also the information pertaining to Definitive Surgical Trauma Skills and I started by giving the ICRC war surgery course to all the surgeons, anaesthetists and medical students that were able to come and listen. They were given tutorials on how to manage the initial casualty situation following ATLS guidelines. All staff collecting patients at the front line were given training in the war the mnemonic (C) ABC the (C) standing for catastrophic haemorrhage and the adage that 'tourniquets save lives' and their application was demonstrated. They were given lectures on how to manage the triage situation on the principles of the ICRC. From a surgical standpoint, it is very difficult to change the perception of the correct surgical management of trauma cases especially to those who have been involved in the situation for a longer period of time than the latest arrival. However, I am indebted to my past military training which helped me to provide command control and leadership skills. There are situations sometimes where arrogance and ignorance need to be very diplomatically sidelined. Surgical teaching was given at the operating table to surgeons on how to manage chest injuries using the correct exposure techniques using either anterolateral or clam-shell thoracotomy. Methods on how to use damage control using arterial shunts followed by external fixation and the correct method of how to carry out a four-compartment fasciotomy were taught. At laparotomy, solid organ management was discussed, the various techniques of exposure such as the Mattox manoeuvre [2] and the Cattel-Braasch manoeuvre [1] were also shown. War orthopaedic management was also changed and orthopaedic surgeons persuaded that all metalwork should be removed and the only way to manage a dirty war wound was by external fixation for those with soft tissue injuries and plaster of Paris and traction for the rest. Another area in war not covered in the trauma skills courses is that of post-conflict surgery. War wounds need continual debridement and also skin cover. A ward was created that specifically offered this surgery. Previously, patients had a painful and miserable journey from Misrata to Benghazi via a sea passage of 24 hours that relied on a ship being able to reach the port. This was mainly for those patients requiring straightforward post-conflict plastic surgery. Simple split skin grafts using dermatomes and meshers were taught to the surgeons. Simple fasciocutaneous flaps to cover exposed limb bones were also demonstrated and taught. Tutorials and live demonstrations on muscle transfers such as soleus and vastus lateralis flaps were also given.

What had originally been a step in the dark for the surgical team arriving in Misrata turned out to be one of the most satisfying missions ever experienced. Having spent many years in conflict zones including Camp Bastian in Afghanistan, placed me in a better position to pass down the correct information to those finding themselves in a war situation for the first time.

It is impossible to extrapolate elective surgical work into the war situation without proper training and instruction and there is no doubt that improvements were made in trauma management during this time. By being able to offer an austere environment training programme to those unfortunate clinical staff that found themselves in a terrible situation dealing with the aftermath of intense bombardment was a truly humbling experience.

References:

- Cattel R. Braasche J. A technique for exposure of the third and fourth portion of the duodenum. Surg Gynaecol Obstet 1960: 11: 379

- Hirshberg A, Mattox KL. The crash laparotomy. In H.Asher 9ed.) The Top Knife, the art and craft of trauma surgery. Tfm Publishing LtD, Castle Hill Barns, Harley, Shrewsbury Harely 53-70 2005.

Â